Japanese Journal of Gastroenterology Research

Research Article - Open Access, Volume 2

Is esomeprazole safe and effective in neonatal gastroesophageal reflux disease? A clinical trial

Peymaneh Alizadeh Taheri1*; Parisa Arab Maghsudi2; Mahbod Kaveh3; Mohsen Vigeh4

1Department of Neonatology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Bahrami Children's Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

2Department of Pediatrics, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Bahrami Children's Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

3Department of Neonatology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Bahrami Children's Hospital, Tehran, Iran

4Department of Epidemiology and Environmental Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Bahrami Children's Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

*Corresponding Author : Peymaneh A Taheri

Bahrami Children Hospital, Shahid Kiai St., Damavand

Ave., Tehran, Iran.

Email: p.alizadet@yahoo.com

Received : Aug 16, 2022

Accepted : Sep 07, 2022

Published : Sep 14, 2022

Archived : www.jjgastro.com

Copyright : © Taheri PA (2022).

Abstract

Introduction: Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is present in pediatric patients when reflux of gastric contents causes troublesome symptoms and/ or complications. GERD is one of the most common referrals to neonatal clinics. There are controversies in the pharmacologic treatment of GERD in neonates.

Aims: There are very few studies that have compared the efficacy of esomeprazole with ranitidine in the management of neonatal GERD, so this study was performed.

Methods: This randomized clinical trial was performed on term neonates with the diagnosis of GERD according to the I-GERQ-R scores who were admitted to Bahrami Children’s Hospital during 2019-2020. One hundred and fourteen term neonates (Mean age 10.4 ± 7.2 days; girls 45%) were randomly assigned to a double-blind trial with either oral ranitidine (group A) or oral esomeprazole (group B). The response rate of the symptoms and signs were recorded after one week and one month of interventions. In the end, fifty neonates in each group completed the study and their data were analyzed.

Discussion: No significant difference in demographic and baseline characteristics were found between the study groups. The response rate of esomeprazole was significantly higher than ranitidine (7.2 ± 2.1 score vs, 9.9 ± 3.8, p<0.001) after one week and (4.2 ± 3.0 score vs 7.9 ± 4.8, score, p<0.001) after one month (primary outcome). No drug side effect was found in either group during the intervention (secondary outcome).

Conclusion: In this study, the response rate was significant in both groups after one week and one month of intervention, but it was significantly higher in the esomeprazole group. This study has been registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trails (RCT20160827029535N3).

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux disease; Term neonates; Ranitidine; Esomeprazole.

Abbreviations: GERD: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease.

Citation: Taheri PA, Maghsudi PA, Kaveh M, Vigeh M. Is esomeprazole safe and effective in neonatal gastroesophageal reflux disease? A Clinical Trial. Japanese J Gastroenterol Res. 2022; 2(12): 1108.

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux is the movement of gastric contents into the esophagus with or without regurgitation/vomiting [1]. When GER results in actual symptoms, it is considered “pathologic GER,” and the condition is known as Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [2]. The actual symptoms of neonatal GERD include recurrent regurgitation or vomiting associated with gastroesophageal symptoms including anorexia, feeding refusal, stop feeding, irritability, excessive crying, failure to thrive, Sandifer syndrome, hematemesis, and anemia. It can also be associated with respiratory symptoms including coughing, choking, wheezing, stridor, apnea, or pneumonia aspiration [3-7]. Epidemiological studies suggest that gastroesophageal reflux occurs in approximately 50% of infants younger than 2 months of age, 60–70% of infants 3–4 months of age, and 5% of infants by 12 months of age [8,9]. GER occurs in approximately 22% of infants born less than 34-week gestation [10]. The diagnosis of GERD is often made clinically but sometimes an upper gastrointestinal series, esophageal impedance-pH monitoring, and endoscopy are needed. In most cases, no treatment is necessary for gastroesophageal reflux apart from reassurance because the condition is benign and self-limiting. The conversive therapy of GERD includes postural change, decreasing the feeding volume, increasing the times of feedings, and milk thickening. Pharmacotherapy (including acid-suppressing drugs such as proton pump inhibitors or H2 blockers, prokinetic agents, and surface barrier agents) should be considered in the treatment of more severe gastroesophageal reflux disease for patients who do not respond to conservative therapy. Surgery is rarely needed [11-13].

There are arguments about pharmacotherapy in neonatal GERD. As far as we know, there are very few studies that have compared the efficacy of PPIs with H2RAs in pediatric and neonatal GERD [14-16]. No study has compared the effectiveness of ranitidine with esomeprazole in neonatal GERD, so the present trial was carried out.

Patients and methods

This double-blind randomized controlled trial was conducted to compare the effectiveness of ranitidine with esomeprazole in neonatal GERD. One hundred and fourteen neonates (postnatal age <28 days, gestational age of 38-40 weeks) referred to Bahrami Children’s Hospital during 2019-2020 with the diagnosis of GERD were assigned in this study. They had responded less than 50% to conservative GERD therapy (including postural change, decreasing the feeding volume, and increasing the times of feedings). The exclusion criteria included: 1- the newborns with any significant malformations or diseases (e.g., major congenital abnormalities, gastrointestinal or neurological diseases, sepsis, cow’s protein milk allergy, etc.), 2- the newborns who required ventilation therapy, 3: the newborns who had received any muscle relaxant or sedative medication. The number of participants was determined by prospective power analysis, assuming a power of at least 80%, a 2-sided alpha of 0.05, and treatment response based on the studies of Hassal et al. [17] and Karjoo et al. [18].

Diagnosis

In this trial, GERD was defined based on the last version of the I-GERQ-R and Validity Clinical Score including twelve items:1- three items of the frequency, amount, and discomfort attributable to spit up, 2-two items of refusal or stopping feeding, 3-three items of crying and fussing, 4- one item of hiccups, 5- one item of arching back, 6- one item of stopping breathing or color change. The total score of I-GERQ-R and Validity Clinical Score ranges from 0 to 42 scores with a a cut point >15 [19]. Other diagnoses were overruled based on the clinical manifestations; lab tests, radiologic findings, etc. The term “resistant to conservative therapy” was utilized if clinical response was less than 50%.

Trial

The proposal of this study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC. 1398.251) and registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trails (RCT20160827029535N3). The parents or guardians of neonates filled out the written informed consent before intervention. They explained the aims of the study and interventions. Mothers were explained that participation was voluntary and the neonates could leave the study at any step of the study. One hundred and fourteen term neonates who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomly assigned (in blocks of two per site) to this study to receive esomeprazole or ranitidine for one month. The random allocation sequence was generated by an independent statistician.

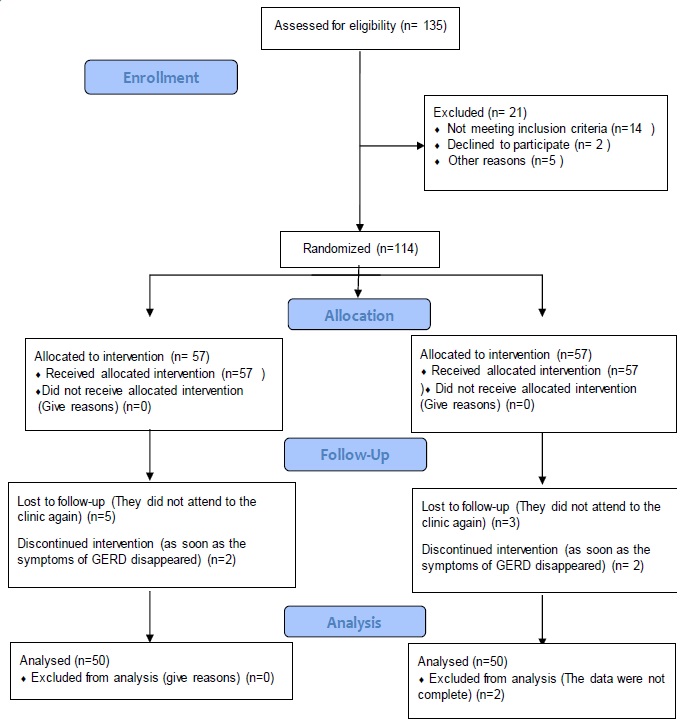

Oral ranitidine was administered 2 mg/kg/dose three times daily to fifty-seven neonates in group A and oral esomeprazole 0.5 mg/kg/dose twice daily to another fifty-seven neonates in group B. The first neonatologist (researcher) recorded the demographic data including age, gender, birth weight, and weight at presentation along with scoring of GERD presentations before intervention. The same neonatologist reevaluated the post-interventional weight and clinical scoring after one week and one month. In each group, seven patients lost to follow-up or discontinued intervention or their data were not complete. In the end, fifty neonates in each group completed the study and their data were analyzed (figure 1). Changes in the scoring of GERD-related clinical presentations from pre-intervention to the end of the study were considered as the primary outcome. The secondary outcome was defined as adverse reactions following oral administration of ranitidine or esomeprazole.

Data analysis

The SPSS for Windows version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was utilized to analyze the data. Descriptive data were announced as Mean and standard deviation (SD) for numerical and number (percent) for categorical data. Post-intervention outputs were analyzed against baseline data using a two-sided paired t-test for differences in the Mean values and chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test (two-sided) for differences in the percentage of response to intervention. A p-value of less than < 0.05 was contemplated significant.

Results

This double-blind randomized trial was performed on100 term newborns (Mean age: 10.4 ± 7.2 days, range: 1-29 days, girls: 45%). The Mean birth weight of patients was 3253.1 ± 329.2 g. All neonates were assessed by the neonatologist. The diagnosis of GERD was made according to the clinical criteria of the I-GERQ-R and Validity Score. The participants were randomized to receive ranitidine (n = 50, ranitidine was administered at a dose of 2 mg/kg/dose three times daily) or esomeprazole (n = 50, esomeprazole was administered at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg/dose twice daily). No significant difference was found in the demographic data of the study groups (Table 1). The participants in both groups were breastfed. The frequency of feeding was every two hours.

Table 1: Demogaphic characteristics in two intervention groups

Demographic characteristics |

Ranitidine (N=50) |

Esomeprazole (N=50) |

P-value |

Gender |

21 (42%) |

24 (48%) |

0.688 |

Age at intervention, mean ± SD, days |

9.7 ± 7 |

11.0 ± 7.4 |

0.375 |

Birth weight, mean ± SD, g |

3214.1 ± 388.8 |

3.292 ± 254.3 |

0.238 |

Weight at presentation, mean ± SD, g |

3274.9 ± .465.6 |

3299.3 ± 450.1 |

0.576 |

Gestational age at birth, mean ± SD, weeks± days |

38w ± 0.8d |

38.2w ± 0.8d |

0.289 |

Total scoring at presentation, mean ± SD |

21.3 + 3.2 |

22.6 + 4.1 |

0.089 |

The pre-interventional Mean ± SD score of clinical manifestations in the ranitidine group was 21.3 ± 3.2 score that declined to 9.9 ± 3.8 score after one week of intervention (intragroup p≤0.001) and to 7.9 ± 4.8 score after one month of intervention (intragroup p≤0.001). The pre-interventional Mean ± SD score of clinical manifestations in the esomeprazole group was 22.6 ± 4.1 that decreased to 7.2 ± 2.1 after one week of intervention ((intragroup p≤0.001) and to 4.2 ± 3.0 after one month of intervention (intragroup p≤0.001) (Tables 2-4).

Table 2: The comparison between GERD-related scoring of clinical manifestations before, one week and one month after intervention.

The mean response rate |

Ranitidine (n=50) |

Esomeprazole (n=50) |

*Intergroup p-value |

Pre-intervention clinical manifestations, scoring, mean± SD |

21.3 ± 3.2 |

22.6 ± 4.1 |

0.089 |

Overall response rate one week after intervention, scoring, mean± SD |

9.9 ± 3.8 |

7.2±2.1 |

≤0.001 |

*** Intra-group p-value |

≤0.001 |

≤0.001 |

|

Overall response rate one month after intervention, scoring, mean± SD |

7.9 ± 4.8 |

4.2 ± 3.0 |

≤0.001 |

*** Intra-group p-value |

≤0.001 |

≤0.001 |

|

Overall response rate one month after intervention, mean± SD |

7.9 ± 4.8 |

4.2 ± 3.0 |

≤0.001 |

***Intra-group p-value |

≤0.001 |

≤0.001 |

|

*Inter-group p Means p between Pre and Post intervention in each group, **Mean of changes (Confidence Interval 95%), ***Intragroup p Means p between two groups of intervention

Table 3: The comparison between GERD-related scoring of clinical manifestations before intervention and one week after intervention.

The mean response rate |

Ranitidine (n=50) |

Esomeprazole (n=50) |

Intergroup p-value |

Pre-intervention clinical manifestations, scoring, mean± SD |

21.3 ± 3.2 |

22.6 ± 4.1 |

0.089 |

Overall response rate one week after intervention, scoring, mean± SD |

9.9 ± 3.8 |

7.2 ± 2.1 |

≤0.001 |

Overall response rate one week after intervention, Percentage |

52.7 ± 17.0 |

66.8 ± 12.4 |

≤0.001 |

Intra-group p-value |

≤0.001 |

≤0.001 |

|

Table 4:The comparison between GERD-related scoring of clinical manifestations before intervention and one month after intervention.

The mean response rate |

Ranitidine (N=50) |

Esomeprazole (N=50) |

Intergroup p-value |

Pre-intervention clinical manifestations, scoring, mean± SD |

21.3 ± 3.2 |

22.6 ± 4.1 |

0.089 |

Overall response rate one month after intervention, scoring, mean± SD |

7.9 ± 4.8 |

4.2 ± 3.0 |

≤0.001 |

Overall response rate one month after intervention, Percentage |

62.1 ± 22.0 |

80.2 ± 16.6 |

≤0.001 |

Intra-group p-value |

≤0.001 |

≤0.001 |

|

On the other hand, the percentage of response rate was significantly higher in the esomeprazole group compared to the ranitidine group after one week (66.8 ± 12.4% vs 52.7 ± 17.0%, intergroup p ≤0.001) and after one month of intervention (80.2 ± 16.6% vs 62.1 ± 22.0%, intergroup p≤0.001.

The Mean (range) of weight gain, gam (g) in ranitidine group was 191.3 g after one week of intervention (p≤0.001) and 876.93 g after one month of intervention (p≤0.001).

The Mean(range) of weight gain in esomeprazole group was 297.9 g after one week of intervention (p≤0.001) and 1007.8 g after one month of intervention (p≤0.001) (Tables 5,6). The findings of this study showed that the response rate was significantly higher in the esomeprazole group compared to the ranitidine group after one week (66.8 ± 12.4% vs 52.7 ± 17.0%, p≤0.001) and after one month of intervention (80.2 ± 16.6% vs 62.1 ± 22.0%, p≤0.001).

Although the mean (range) of weight gain was significant in both groups after one week (intra-group p≤0.001), and after one month of age (intra-group p ≤0.001); the mean (range) of weight gain was not significant between the two groups after one week (intergroup p =0.125) and after one month of age (intergroup p =0.098).

Table 5: The comparison of body weight before intervention and its changes relative to one week and one month after intervention.

Bodyweight |

Ranitidine (N=50) |

Esomeprazole (N=50) |

P-value |

Pre-intervention bodyweight, g mean± SD |

3247.9 ± 465.6 |

3299.3 ± 450.1 |

0.576 |

Bodyweight, g one week after intervention mean± SD |

3439.2 ± 494.6 |

3597.2 ± 525.0 |

0.125 |

Bodyweight, g one month after intervention mean± SD |

4124.8 ± 559.4 |

4307.1 ± 531.5 |

0.098 |

*Mean (range) of changes (Confidence Interval 95%)*

Table 6: The comparison of bodyweight before intervention with one week and one month after intervention.

Bodyweight |

Ranitidine (n=50) |

Esomeprazole (n=50) |

Intergroup p-value |

Pre-intervention bodyweight, g, mean± SD |

3247.9 ± 465.6 |

3299.3 ± 450.1 |

0.576 |

Bodyweight, one week after intervention, g, mean± SD |

3439.2 ± 494.6 |

3597.2 ± 525.0 |

0.125 |

Intra-group p-value |

≤0.001 |

≤0.001 |

|

Pre-intervention bodyweight, g, mean± SD |

3247.9 ± 465.6 |

3299.3 ± 450.1 |

0.576 |

Bodyweight, one month after intervention, g, mean± SD |

4124.8 ± 559.4 |

4307.1 ± 531.5 |

0.098 |

Intra-group p-value |

≤0.001 |

≤0.001 |

|

Bodyweight, one week after intervention, g, mean± SD |

3439.2 ± 494.6 |

3597.2 ± 525.0 |

0.125 |

Bodyweight, one month after intervention, g, mean± SD |

4124.8 ± 559.4 |

4307.1 ± 531.5 |

0.098 |

Intra-group p-value |

≤0.001 |

≤0.001 |

|

Discussion

This study was performed to compare the effectiveness and safety of oral ranitidine with oral esomeprazole in the treatment of neonatal GERD resistant to conservative therapy. In apposite to less evidence for amended outcomes and increasing worries over side effects in children and infants less than 12 months of age, oral PPIs have been used widely for the treatment of GERD in this age group [19,20]. PPIs have been associated with less therapeutic disruption and less therapeutic changes in the first month of treatment [19]. The first therapeutic approach for infantile GERD was a “step-up” regimen of acid suppression therapy. In the first step, ranitidine is administered. If the patient does not respond to high dose ranitidine, it is replaced with PPIs [21]. An updated review on GERD in children showed that pharmacotherapy should be started if the patient with severe GERD does not respond to conservative therapy. PPIs have been more effective than H2-receptor antagonists [22]. A few studies have compared PPIs with H2RAs in this age group, PPIs have been used rarely as the first acid suppressant for the treatment of infantile and neonatal GERD [14-16].

Few researchers have studied the efficacy of esomeprazole in the treatment of GERD in infants, and neonates including [14,23-26]:

1-Omari T et al studied the pharmacokinetics and acid-suppressive effects of esomeprazole in infants 1 to 24 months old with symptoms of GERD. They administered oral esomeprazole 0.25 mg/kg to 26 infants or 1 mg/kg to 24 infants (once daily) who had intraesophageally pH <4 (≥5% of the time) in 24-hour of dual pH monitoring. After one week, the intraesophageally and intragastric pH were recorded and pharmacokinetic analysis of blood sampling was performed. Their study showed esomeprazole 0.25 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg were well tolerated and declined the dose-related esophageal acid exposure in these infants [23].

2-Winter et al surveyed the efficacy and safety of weight-adjusted doses of esomeprazole (2.5-10 mg) or placebo for 4 weeks once daily in infants ages 1 to 11 months with GERD in a multicenter randomized, double-blind study. The physician global assessment (PGA) showed symptom improvement in 81 (82.7%) of the 98 patients during two weeks of intervention and 80 patients entered the double-blind phase. During this phase, omeprazole was discontinued due to symptom worsening in 38.5% of patients versus 48.8% in the placebo group (p = 0.28) but the time of discontinuation was significantly longer with esomeprazole than with placebo (p=0.01). Esomeprazole was well tolerated. Their study suggests that it is necessary to introduce improved diagnostic criteria to identify infants with GERD in this age group who may benefit from acid suppression therapy [24].

3-Abbasi et al performed a randomized double blinded clinical trial on 90 infants of 2-24 month-old with the diagnosis of GERD. They were randomly participated to three intervention groups (30 cases in each group). Each group received lansoprazole or omeprazole with a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight /day. The patients were evaluated on the basis of GERD-Q questionnaire before and after two and four weeks of intervention. Their study showed that there was no significant difference in the response rate of lansoprazole, omeprazole, and esomeprazole. Although the three PPIs were effective on GERD recovery 2 weeks and 4 weeks after the intervention, esomeprazole had a higher and faster effect on recovery of the symptoms of GERD [24].

4-Davidson et al performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study in neonates (premature to 1 month corrected age; n = 52) with signs and symptoms of GERD who received esomeprazole 0.5 mg/kg or placebo once daily for up to 14 days. The percentage change from baseline in the total number of GERD-related clinical manifestations was not significant between esomeprazole and placebo (-14.7% vs -14.1%, respectively). Esomeprazole did not change the total number of reflux episodes significantly versus placebo (-7.43 vs -0.2, respectively); however, it declined the percentage of time pH 5 minutes in duration significantly vs placebo (-10.7 vs 2.2 and -5.5 vs 1.0, respectively; p ≤ .0017) [26].

5- AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals did a clinical study of administering esomeprazole to infants less than one year of age with the diagnosis of GERD for 7 days and compared it with adults. They showed that administering of esomeprazole with the dose of 0.5 mg/kg to the infants <1 month of age and 1.0 mg/kg to the infants 1 to 11 months old infants could change the percentages of time with intragastric pH >4 higher (84.7% and 68.6% respectively) than those reported for adult GERD patients on esomeprazole 20 mg (52.7%). There was no “volume” change of reflux measured by intramural impedance monitoring in this study [14]. A far as we know, there is no study that has compared ranitidine with esomeprazole in the management of neonatal GERD resistant to conservative therapy, so this study was carried out. The findings of our study showed that the response rate was significantly higher in the esomeprazole group compared to the ranitidine group after one week (66.8 ± 12.4 vs 52.7 ± 17.0, p≤0.001) and after one month of intervention (80.2 ± 16.6 vs 62.1 ± 22.0, p≤0.001). Although the Mean (range) of weight gain was significant in both groups after one week (intra-group p≤0.001), and after one month of age (intra-group p ≤0.001); the Mean (range) of weight gain was not significant between the two groups after one week (intergroup p=0.125) and after one month of age (intergroup p =0.098).

Omari et al, Winter et al, and Abbasi et al studied the effects of esomeprazole in infants >1 to 24 months old with symptoms of GERD. The age group of our study was less than one month on newborn infants. Omari et al, Davidson et al, and AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals studied on neonates. Their studies showed that administering of esomeprazole changed the percentages of time with intragastric pH >4 significantly higher than placebo but did not change the total number of reflux episodes and the total number of GERD-related clinical manifestations versus placebo significantly. In contrast to their studies, the clinical response rate and weight gain were significantly high in both groups of ranitidine and esomeprazole after one week and after one month of intervention in our research. Our findings showed that the clinical response rate and weight gain were even significantly higher in esomeprazole group. The administered dose of esomeprazole in our study was the same (1 mg/kg/day) as the surveys of Omari et al but the administered dose of esomeprazole in the studies of Davidson et al, and AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals was lower(0.5 mg/kg/day).

Some studies have shown that acid suppressants may lead to higher infection rates, necrotizing enterocolitis, and mortality in neonates, especially in premature infants [27-29]. Kierkus et al. showed that PPIs were well tolerated in short-term administration with mild to moderate side effects in pediatrics [30], but more surveys should be performed to establish the efficacy and safety of acid suppressants in infants [20].

In our study, no side effect was found in the ranitidine or esomeprazole group. Similar studies with more participants are recommended to determine the efficacy of PPIs in neonatal GERD.

Conclusion

This study showed that the response rate was significant in each group after one week and one month of treatment, but it was significantly higher in the esomeprazole group.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest: All Authors declare that they have nothing to disclose, financially or otherwise. There is no conflict of interest. This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements: The Authors wish to thank the personnel of Neonatal Clinic and Neonatal Ward of Bahrami Children Hospital. We also express our gratitude to the Research Development Center of Bahrami Children Hospital.

Funding: No sources of funding were used to conduct this study or prepare this manuscript.

References

- Hegar B, Dewanti NR, Kadim M, Alatas S, Firmansyah A, Vandenplas Y. Natural evolution of regurgitation in healthy infants. Acta Paediatr. 2009; 98: 1189-93.

- Ciciora1 SL, Woodley FW. Optimizing the use of medications and other therapies in infant gastroesophageal reflux. Paediatr Drugs.2018; 20: 523–537.

- Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, Cabana M, Carlo Di Lorenzo, Gottrand F, et al.Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018; 66: 516–554.

- Lightdale JR, Gemse DA. Section on gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition. Gastroesophageal Reflux. Management guidance for the pediatrician. J Pediatr. 2013; 131: e1684-95.

- Randel A: AAP releases guideline for the management of gastroesophageal reflux in children. Am Fam Physician. 2014; 89: 395-7.

- Sherman PM, Hassall E, Fagundes-Neto U, Gold BD, Seiichi Kato S, Koletzko S, et al. A global, evidence-based consensus on the definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the pediatric population. Am J Gastroenterol.2009; 104: 1278–1295.

- Orenstein SR, McGowan JD. Efficacy of conservative therapy as taught in the primary care setting for symptoms suggesting infant gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr. 2008; 152: 310–314.

- Dranove JE. New technologies for the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Pediatr Rev. 2008; 29: 317–320.

- Nelson SP, Chen EH, Syniar GM, Christoffel KK. Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during infancy. A pediatric practice-based survey. Pediatric Practice Research Group . Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997; 151: 569–572.

- Dhillon AS, Ewer AK. Diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux in preterm infants in neonatal intensive care units. Acta Paediatr. 2004; 93: 88–93.6.

- Leung AKC, Hon KL. Gastroesophageal reflux in children: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2019; 8: 212591.

- Badran EF, Jadcherla S. The enigma of gastroesophageal reflux disease among convalescing infants in the NICU: It is time to rethink. Int. J. Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2020; 7: 26-30.

- Ayerbe JIG, Hauser B, Salvatore S, Vandenplas Y. Diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in infants and children: from guidelines to clinical practice. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2019; 22: 107-121.

- Aztra Zeneca. Briefing document for the gastrointestinal drugs advisory committee meeting. Clinical experience related to the esomeprazole clinical studies in patients. 2010.

- Taheri PA, Mahdianzadeh F, Shariat M, Manelie Sadeghi M: Combined therapy in gastro-esophageal reflux disease of term neonate resistant to conservative therapy and monotherapy: a clinical trial. JPNIM. 2018; 7: e070201.

- Azizollahi HR, Rafeey M. Efficacy of proton pump inhibitors and H2 blocker in the treatment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease in infants. Korean J Pediatr 2016; 59: 226-230.

- Hassall E, Israel D, Shepherd R, Radke M, Dalväg A, Sköld B,et al. Omeprazole for treatment of chronic erosive esophagitis in children: a multicenter study of efficacy, safety, tolerability and close requirements. J Pediatr. 2000; 137: 800–807.

- Karjoo M, Kane R. Omeprazole treatment of children with peptic esophagitis refractory to ranitidine therapy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. .1995; 149: 267–271.

- Nelson SP, Kothari S, Wu EQ, Beaulieu N, McHale JM, Dabbous OH. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux disease and acid-related conditions: trends in incidence of diagnosis and acid suppression therapy. J Med Econ. 2009; 12: 348-55.

- Barron JJ, Tan H, Spalding J, Bakst AW, Singer J. Proton pump inhibitor utilization patterns in infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007; 45: 421-7.

- Hassall E. Step-down approaches to treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008; 10: 324-31.

- Leung AKc, Hon KL. Gastroesophageal reflux in children: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2019; 8: 212591.

- Omari T, Davidson G, Bondarov P, Nauclér E, Nilsson C, Lundborg P. Pharmacokinetics and acid-suppressive effects of esomeprazole in infants 1-24 months old with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007; 45: 530- 7.

- Winter H, Gunasekaran T, Tolia V, Gottrand F, Barker PN, Illueca M. Esomeprazole for the treatment of GERD in infants ages 1-11 months. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Jul; 55: 14-20.

- Abassi R, Abassi F, Mosavizadeh A, Sadeghi H, Keshtkari A. Comparison the effect of omeprazole, esomeprazole and lansoprazole on treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in infants. Int J Clin Ski. 2020; 1: 127-132.

- Davidson G, Wenzl TG, Thomson M, Omari T, Barker P, Lundborg P, Illueca M. Efficacy and safety of once-daily esomeprazole for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in neonatal patients. J Pediatr. 2013; 163: 692-8. e1-2.

- Terrin G, Passariello A, De Curtis M, Manguso F, Salvia G, Lega L, et al. Ranitidine is associated with infections, necrotizing enterocolitis, and fatal outcome in newborns. Pediatrics. 2012; 129: e40-5.

- Santos VS, Freire MS, Santana RNS, Martins-Filho PRS, Cuevas LE, Ricardo Q, et al. Association between histamine-2 receptor antagonists and adverse outcomes in neonates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019; 14: e0214135.

- Santana RNS, Santos VS, Ribeiro-Júnior RF, Freire MS, Menezes MAS, Cipolotti R, et al. Use of ranitidine is associated with infections in newborns hospitalized in a neonatal intensive care unit: a cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017; 17: 375.

- Kierkus J, Oracz G, Korczowski B, Szymanska E, Wiernicka A, Woynarowski M. Comparative safety and efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in paediatric gastroesophageal reflux disease. Drug Saf. 2014; 37:309-16.