Japanese Journal of Gastroenterology Research

Case Series - Open Access, Volume 2

CT evaluation of different forms of abdominal tuberculosis: A series of multiple cases

Kritika1 ; Rajaram Sharma2 *; Tapendra Tiwari2 ; Saurabh Goyal2

1Resident Doctor, Pacific Institute of Medical Sciences, Umarda, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India-313001.

2Assistant Professor, Pacific Institute of Medical Sciences, Umarda, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India-313001.

*Corresponding Author : Rajaram Sharma

Assistant professor, Radio-diagnosis Pacific Institute

of Medical Sciences (PIMS), Umarda, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India-313001.

Tel: +91-7755923389;

Email: hemantgalaria13@gmail.com

Received : May 17, 2022

Accepted: Jun 17, 2022

Published : Jun 22, 2022

Published: Jun 24, 2022

Copyright : © Sharma R (2022).

Abstract

Tuberculosis infection has a high incidence in the immunocompromised individual or patients with pre-existing illness or undergoing any immunosuppression. Although many cases of abdominal tuberculosis are found to be due to pulmonary causes, when the infective organism is swallowed with the cough, abdominal tuberculosis has many presentations and can mimic inflammatory bowel disease, cancer and other infectious diseases, which causes a delay in the diagnosis resulting in significantly increased morbidity. Therefore, early detection of infection is of utmost importance for the proper treatment. This pictorial essay portrays the common presentation of abdominal tuberculosis utilizing computed tomography scans and demonstrates different imaging features and involvement of various viscera.

Keywords: Tuberculosis; Abdomen; Computed tomography.

Citation: Kritika, Sharma R, Tiwari T, Goyal S. CT evaluation of different forms of abdominal tuberculosis: A series of multiple cases. Japanese J Gastroenterol Res. 2022; 2(9): 1090.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a commonly found infectious disease caused by the bacillus Mycobacterium, and for abdominal infection, M. Bovis is mainly responsible [1]. It has been the leading cause of infection in developing countries since the mid-1980s. It is responsible for millions of deaths worldwide (Approximately 5.8 million people developed TB in 2020) [2]. This symptomatic infection is mainly associated with the immune status of the individual. The primarily involved organ is the lung, but many patients are reported in the literature with extrapulmonary involvement. Approximately 15% of all extrapulmonary TB infections, 11 to 12% cases have abdominal involvement [3,4]. The abdominal infection may involve different structures such as the gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, organs like liver, spleen, pancreas, gallbladder, peritoneum and lymph nodes or involvement of one or two organs simultaneously. This disease can mimic conditions like an inflammatory disease of GIT (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis), amebiasis or adenocarcinoma. Abdominal tuberculosis presents with many non-specific symptoms like pain abdomen (60%), fever (75%), weight loss (36%) and features related to peritonitis. Due to this diagnostic dilemma, diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis can be challenging; therefore, detailed radiological investigations are essential. CT scan has an advantage in the evaluation of abdominal tuberculosis as it can scan the abdomen in a single examination and has better visualization.

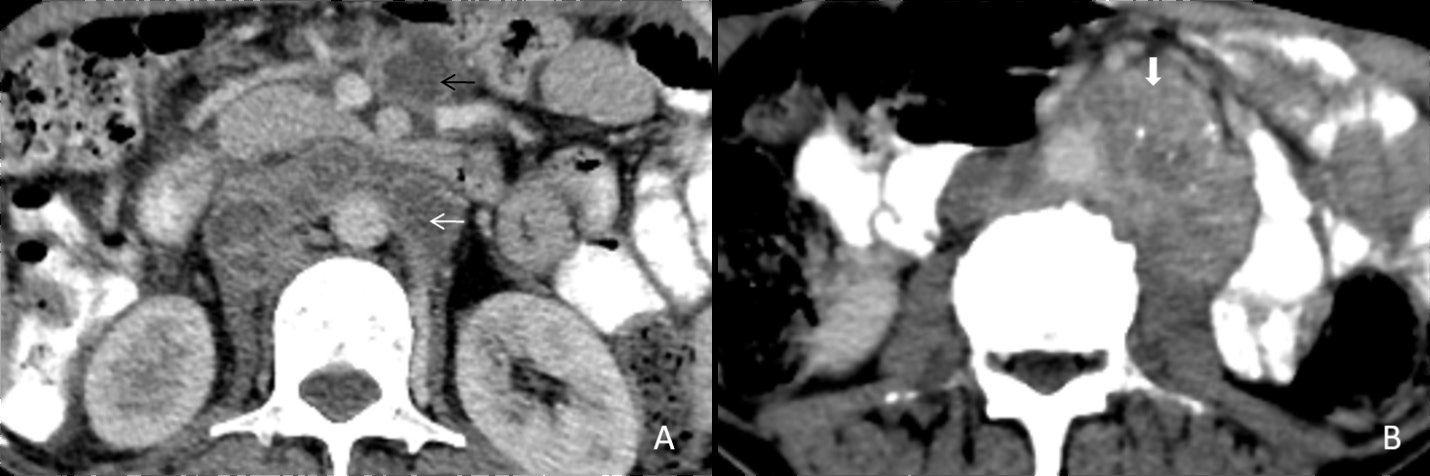

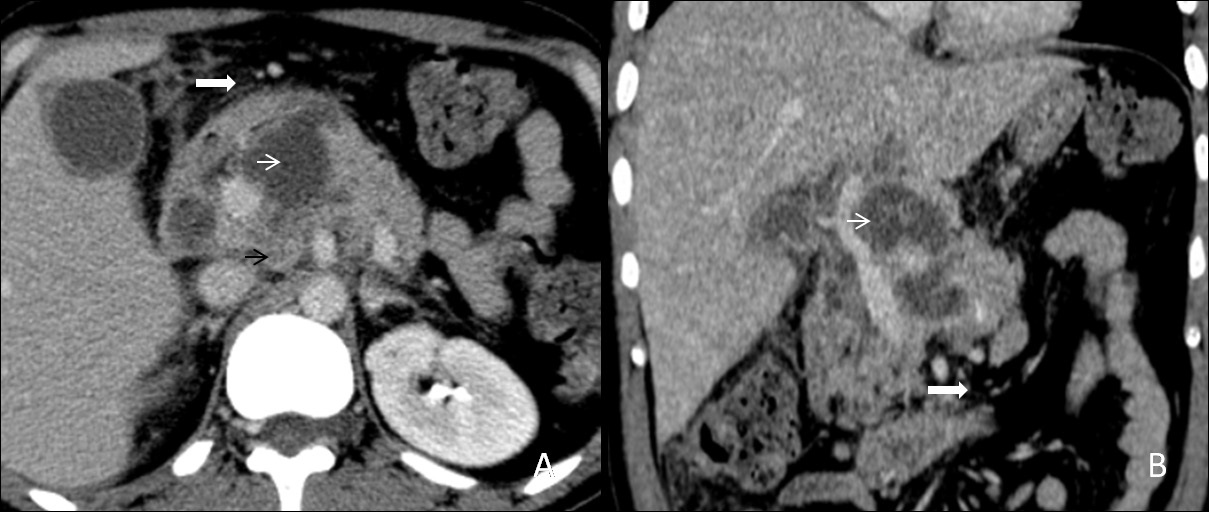

Tubercular lymphadenitis

Lymphadenopathy is the commonest finding associated with abdominal tuberculosis. A wide range of patterns can be seen, including an increase in the number of lymph nodes to large nodal masses. The commonly involved lymph nodes groups are omental, mesenteric, celiac, portahepatis and peripancreatic. The conglomerated pattern of lymph nodes is commonly seen in abdominal tuberculosis. In contrast, CT features of involved lymph nodes may vary from peripherally enhancing lymph nodes with low-density centres (signifies caseous necrosis) to homogeneous/heterogeneous enhancement. Lymph nodes calcification is also seen in chronic tubercular infection (Figure 1A,1B). The necrotic lymph nodes are not pathognomic for tuberculosis as they can also be seen in metastasis, lymphoma or Whipple’s disease [4].

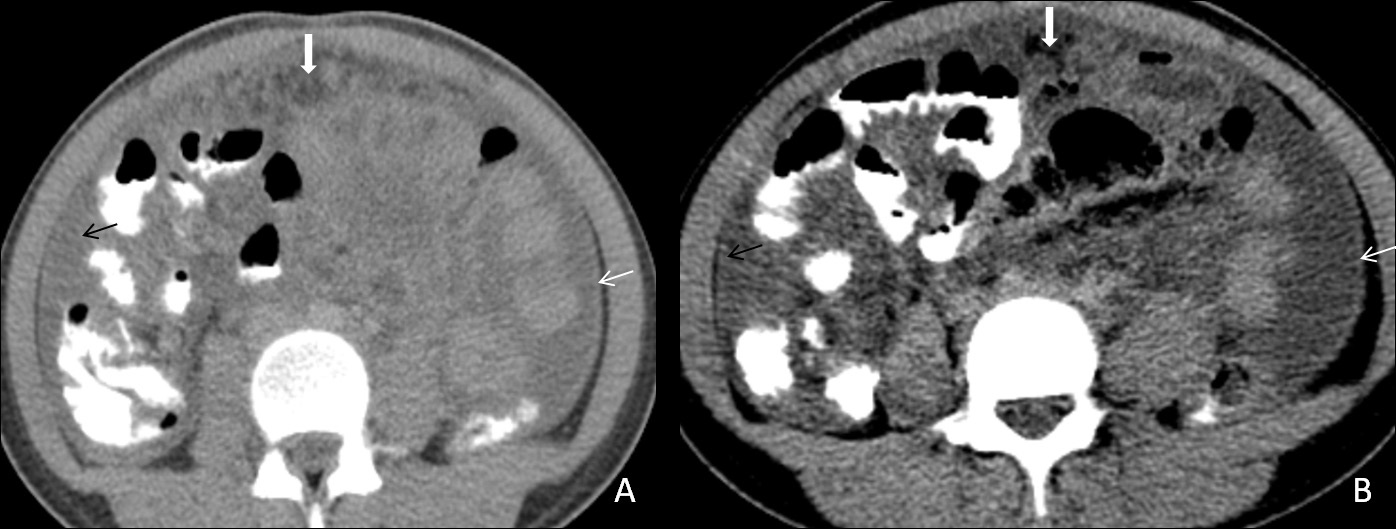

Tubercular peritonitis

Peritoneal involvement is frequently seen in all forms of abdominal tuberculosis. There are three main types of tubercular peritonitis is given [5]. (A) The wet type is in which a large amount of free or loculated viscous fluid is seen. CT findings in this type of peritonitis include high attenuation free fluid (HU value between +25 to +45; signifies high protein and cellular content), (B) the fibrotic fixed type of peritonitis, which is less common and is marked by omental masses, matted mesentery or bowel loops and sometimes loculated ascites, (C) the dry or plastic-type, which is unusual and on CT scan it appears as caseous nodules, fibrous peritoneal reaction, and adhesions. All these described CT features may be confused with peritoneal carcinomatosis [6]. Therefore few features like minimal thickening and enhancement signify TB peritonitis, (Figure 2A,2B) while nodular or irregular thickening implies carcinomatosis. TB peritonitis has a few other findings like macronodular mesenteric deposits (>5 mm), fibrous wall covering the omentum (cocoon abdomen) (Figure 2), and peritoneal or extraperitoneal masses with internal calcifications. Few studies also state that the spreading of inflammation through the peritoneal to the extraperitoneal compartment is specific for TB infection [7].

GI tract

Involvement of the stomach and duodenum is extremely rare due to the lack of lymphoid tissue around these. If tubercular gastritis occurs, it mainly involves the antrum or distal part of the stomach and causes an irregular, nodular wall thickening ulceration and may lead to gastric outlet obstruction. These features may mimic other conditions like syphilis, lymphoma, radiation and corrosive gastritis. Duodenum is also a rare site of tubercular infection, and its imaging features are wall thickening, fistula tract formation, and ulceration which may mimic Crohn’s disease. The differential points are the larger extent of wall thickening and ulceration in tuberculosis as compared to Crohn’s disease [8].

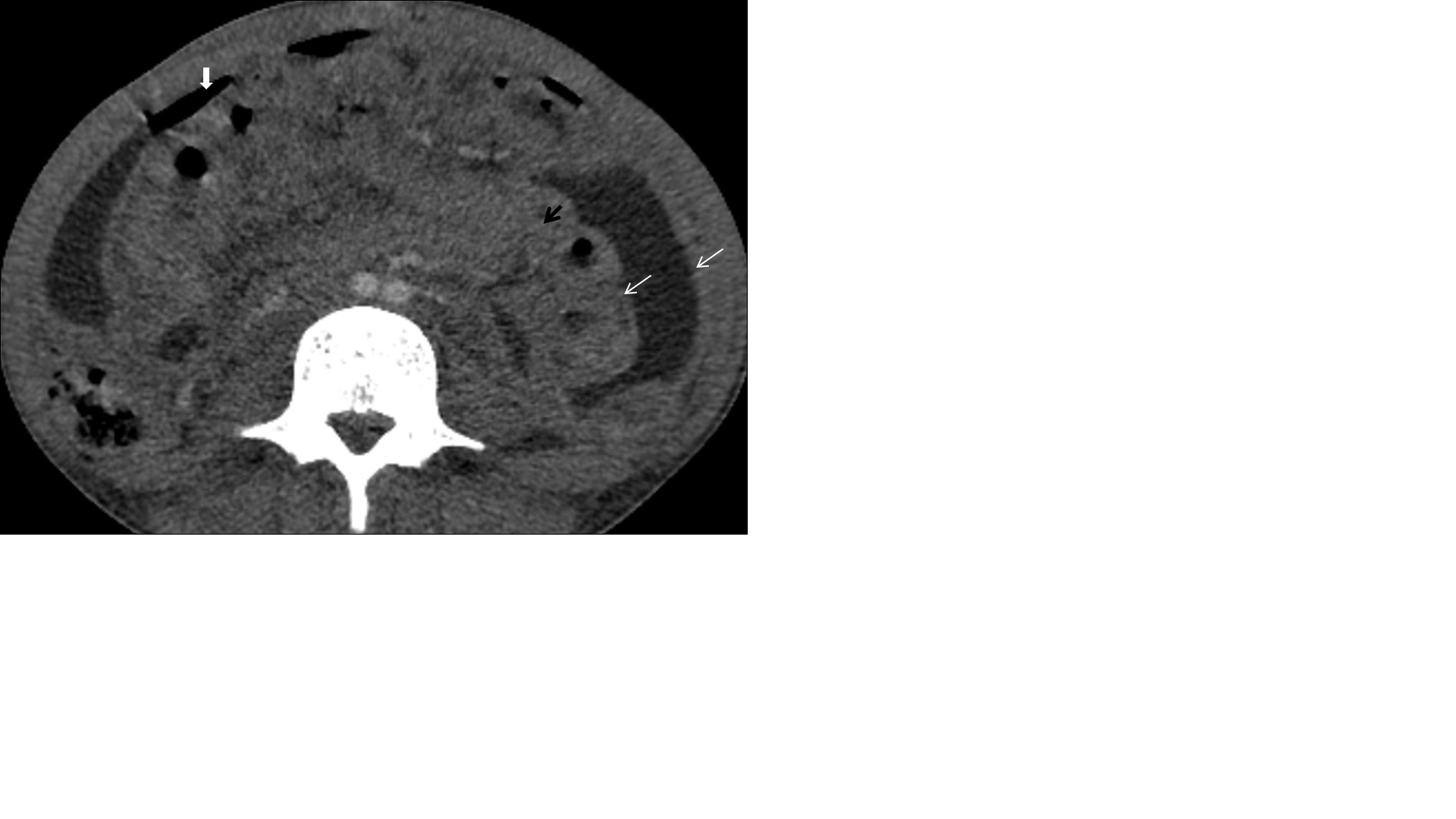

Primary intestinal involvement in tuberculosis is uncommon. The gastrointestinal involvement occurs through ingestion of infective organism with sputum or food via hematogenous route or direct spread from the adjacent organ. Tuberculosis is the infection which can involve any segment of the gastrointestinal tract and in colon it forms coccon formation (Figure 3) and the ileocaecal valve, terminal ileum and caecum are found to be more commonly involved; in approximately 90% of intestinal tuberculosis (Figure 4A,4B), it cal also involved colon part as one of our patient has ascending colon thickening and came out to be tubercular (Figure 5). Rectal involvement in tuberculosis is also rare, which represents fistula formation or fibrosis with rectal inflammation. Clinical presentations of rectal tuberculosis are hematochezia and constipation.

Major imaging findings seen in the intestine are symmetrical or asymmetrical bowel wall thickening, fistulae, altered enhancement, or mesenteric fat stranding and strictures are seen in chronic infection. A pulled up caecum is seen into the right subhepatic space due to retraction of the surrounding mesentery. A conglomeration of findings such as asymmetry of the ileocecal valve, the cecal wall thickening, intra-caecal absorption of the terminal ileum, along lymphadenopathy is evocative of tuberculosis [4]. When tuberculosis is suspected, a surgical biopsy should be done to establish the diagnosis.

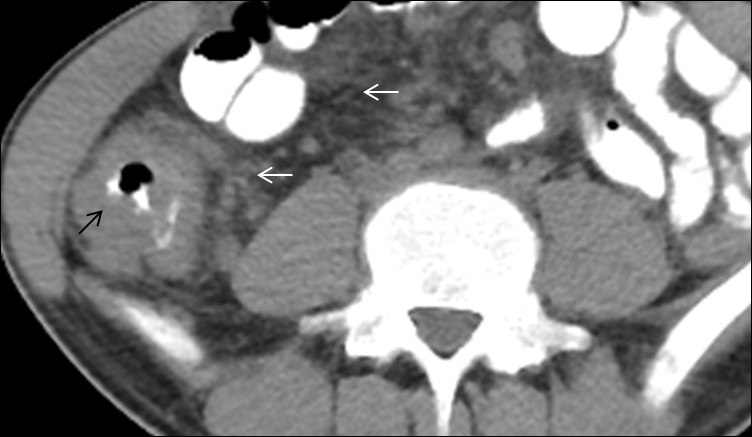

Tubercular appendicitis

Tubercular appendicitis is usually mistaken as bacterial appendicitis or any other inflammatory disease. The infection can lead to perforation; therefore, it is advisable to remove the appendix in all abdominal tuberculosis patients undergoing surgery for any reason (Figure 6A,6B,6C).

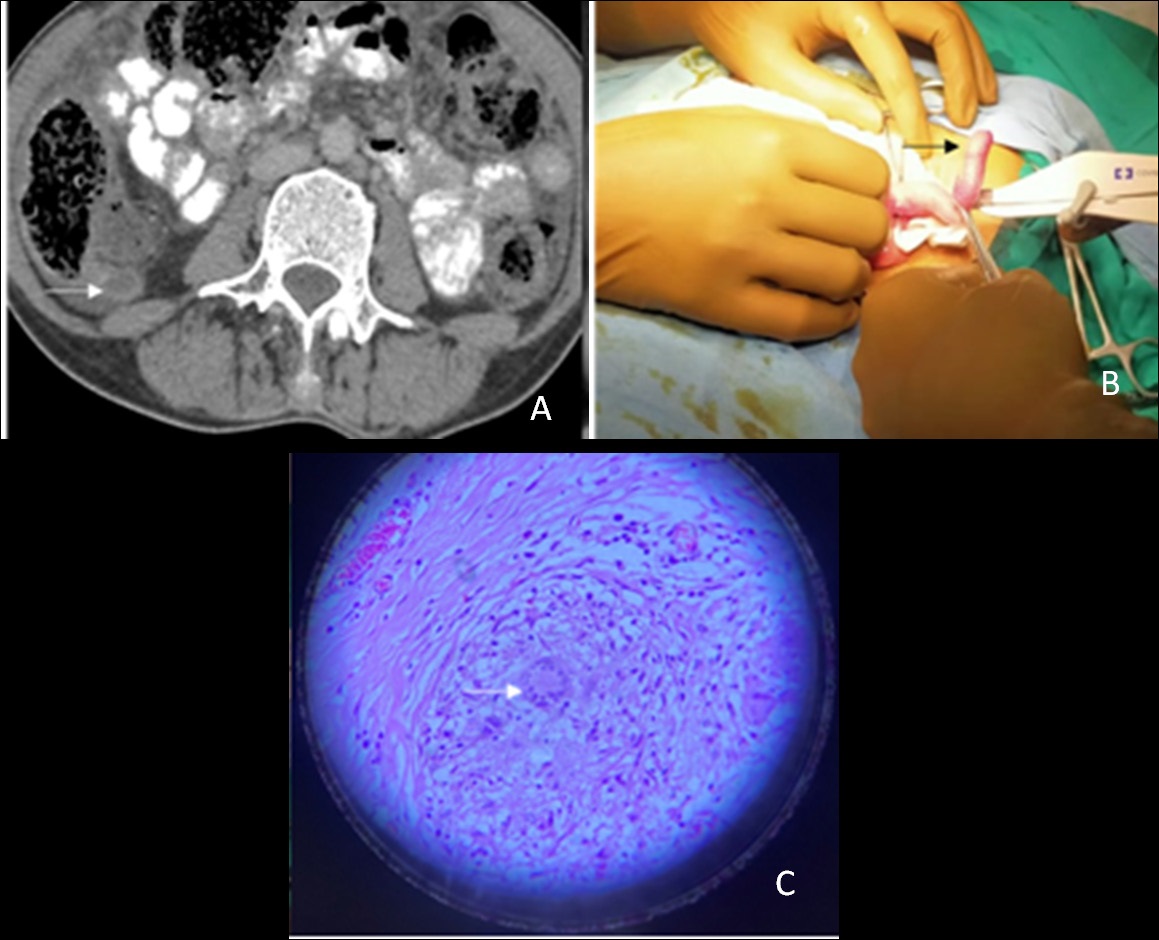

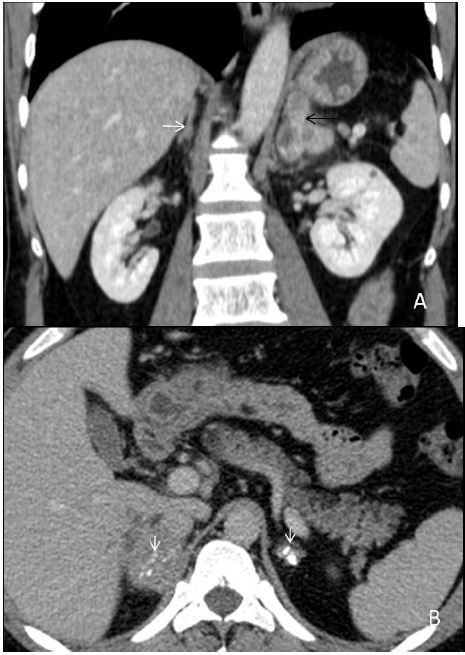

Hepatosplenic tuberculosis

Isolated hepatic or splenic involvement is rare in tubercular infection. It is almost every time associated with the lung or involvement of another abdominal organ. Mainly two broad types of features are there in hepatic or splenic tuberculosis, i.e. military or macronodular. The miliary type is associated with hematogenous dissemination, therefore involving the whole liver or spleen, resulting in liver/spleen enlargement and deranged liver functions. Whereas in macronodular type, dissemination is through a portal vein in which multiple hypodense lesions are observed scattered diffusely in the liver or spleen (Figure 7A). Calcification can also be seen in the chronic phase (Figure 7B). These macronodular presentations may confuse with abscess or metastasis. The involvement of the biliary tree by tuberculosis is even rarer, and its annual incidence is estimated to be 0.1%. If the biliary tree is involved, it is secondary to compression by hepatic granulomas. The gall bladder is rarely involved.

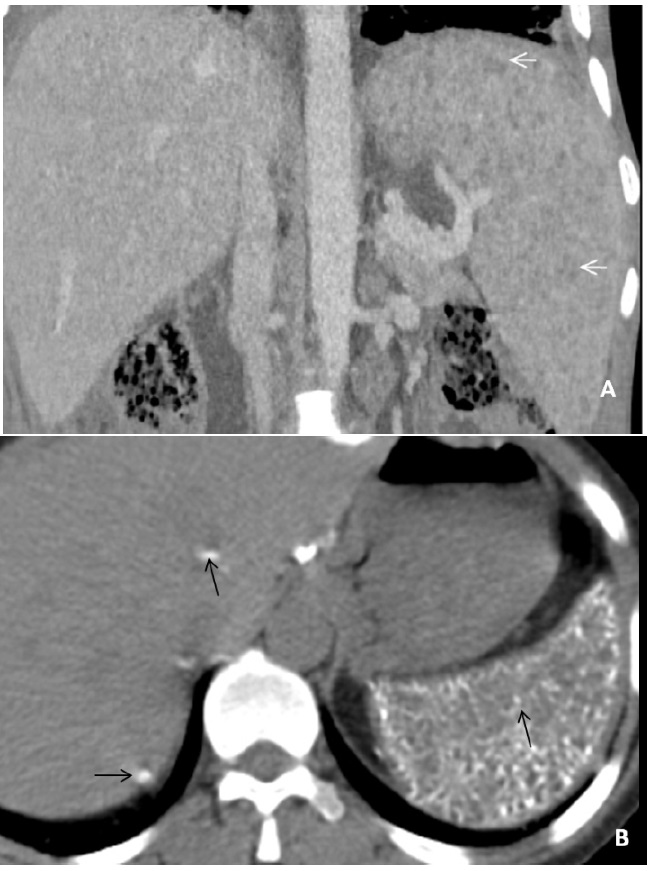

Adrenal tuberculosis

In about 10-30% of cases of Addison disease, adrenal tuberculosis is the most common infection found. The CT appearance of tubercular infection depends on its course and inflammatory process. CT findings of early tubercular infection in adrenal are typical bilateral adrenal enlargement with central necrosis (appears hypoattenuating on CT) with the peripheral enhancing rim (Figure 8A). In the late stages of the disease, the adrenal gland appears calcified and atrophic (Figure 8B).

Pancreatic tuberculosis

Isolated tuberculosis of the pancreas is rare, even in countries with a high prevalence of tuberculosis. Pancreatic tuberculosis represents solitary or multiple lesions with multiple necrotic areas. It usually occupies the pancreatic body or head, (Figure 9A,9B) and peripancreatic lymphadenopathy can also be found. The cystic component appears hypoechoic (sometimes hypo-isoechoic) on ultrasound and hypodense on CT scan [9].

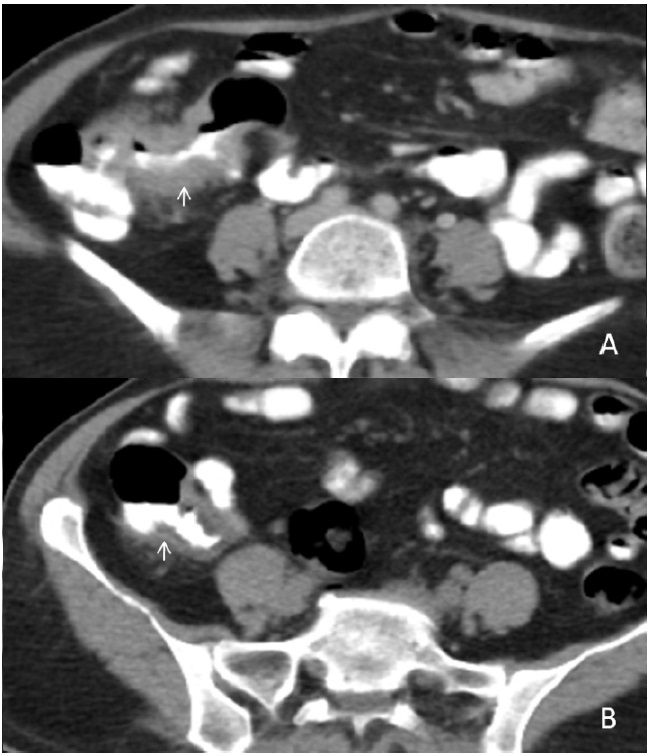

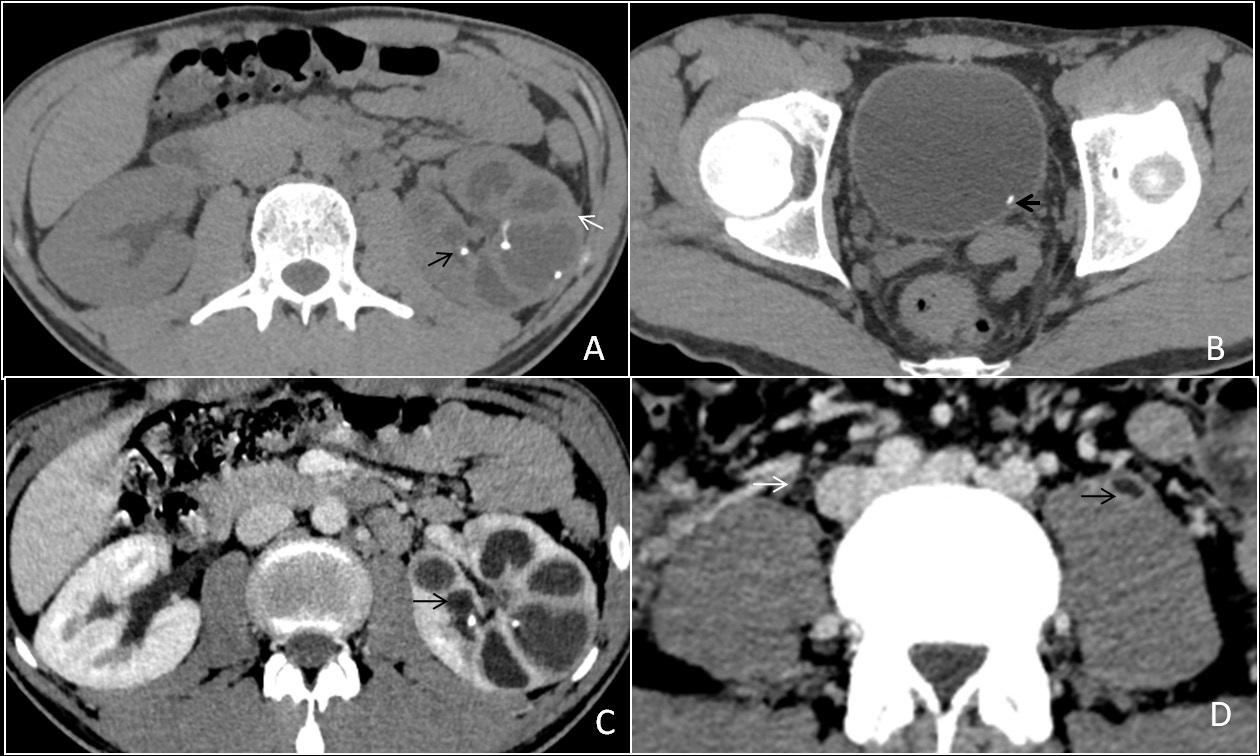

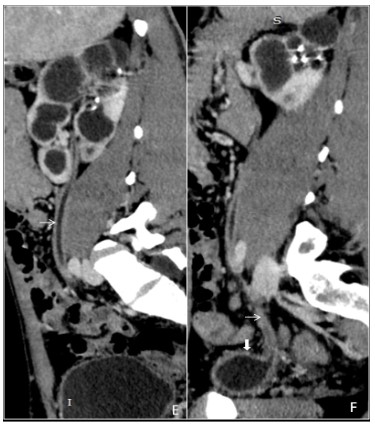

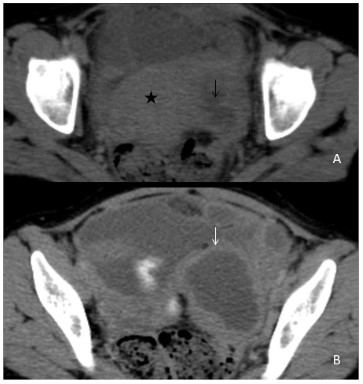

Genitourinary tuberculosis

Genitourinary tuberculosis is the second most common site of tuberculosis, caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, secondly to pulmonary tuberculosis. It can be divided anatomically into renal tuberculosis (renal parenchyma, calyces and renal pelvis), bladder and ureteric tuberculosis, prostatic tuberculosis, scrotal tuberculosis, tuberculous pelvic inflammatory disease (female). The kidneys are the most common site of GUTB. Clinical presentations are hematuria, frequency, urgency, dysuria with involvement of the bladder. Stricture formation is the most common complications in GUTB. Common sites of stricture formations are the neck of a calyx causing hydrocalyx, regional hydro calcinosis, pelvic-ureteric junction causing generalized dilatation of pelvicalyceal system and lower end of the ureter. Other imaging findings are parenchymal scars & irregularity of the papillary tips (motheaten calices), and small cavities in the papillae. (Figure 10A,10B,10C,10D) Sometimes fibrotic reactions may develop, leading to stenosis and strictures formations. Chronic tubercular infections in the genitourinary tract result in a ‘thimble bladder’ appearance and patulous VUJ (Figure 10E,10F). In females, pelvic tuberculosis is seen commonly in India, leading to a tubo-ovarian abscess or stricture formation (Figure 11A,11B).

Conclusion

1. In a suspected case of abdominal tuberculosis computed tomography scan of the abdomen is the choice of modality to differentiate.

2. Tuberculosis has a great prevalence in India, and it has a broad spectrum of imaging; therefore, proper imaging plays an important role in making timely diagnoses.

References

- Raviglione MC. Snider DE Jr. Kochi A. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis: morbidity and mortality of a worldwide epidemic. JAMA

- Global tuberculosis report 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

- LingenfelserT, Zak J, Marks IN, Steyn E Halkett J. Price SK. Abdominal tuberculosis: still a potentially lethal disease. Ant .1 Gasteroenterol 1993; 88: 744-750.

- Leder RA. LOW VHS. Tuberculosis of the abdomen. Radiol Clin,, North ,4iii 1995; 33: 691-705.

- Denton T. Hossain J. A radiological study of abdoniinal tuberculosis in a Saudi population. With special reference to ultrasound and computed tomography. Clin, Radiol 1993; 47: 40-f14.

- Rodriguez E. Pombo F. Peritoneal tuberculosis versus peritoneal carcinomatosis: distinction based on CT findings 1996; 20: 269- 272.

- Ha HK.JungJI. Lee MS.et al.CTdifierentiationof tuberculous peritonitis and pentoneal carcinoniatosis.. AJR. 1996; l67: 743-748.

- Kedar RP. Shah PP. Sliivde RS. Malde HM. Sonographic findings in gastrointestinal and peritoneal tuberculosis. Clin Radiol. 1994; 49: 24-29.

- Reeder MM, Palmer PES. Infections and infestations. In: Freeney PC, Stevens in GW. eds. Alintentars tract radiology. St. Louis: Mosby.