Japanese Journal of Gastroenterology Research

Case Series - Open Access, Volume 2

A woman hemophilia carrier with life-threatening esophageal varices and a severe hemophiliac male: A comparison of two different case reports and a brief description of literature

Samantha Pasca1,2*; Silvano Fasolato3; Lino Polese4; Ezio Zanon5

1Department of Biomedical Sciences (DSB), Padua University Hospital, Italy

2Department of Medicine (DIMED), Padua University Hospital, Italy.

3Medical Emergencies in Liver Transplantation Unit, Padua University Hospital, Italy.

4Department of Gastroenterological and Surgical Sciences, Padua University Hospital, Italy.

5General Medicine, Hemophilia Center, Padua University Hospital, Italy.

*Corresponding Author : Samantha Pasca

Department of Biomedical Sciences (DSB), Padua

University Hospital, Italy.

Email: sampasca27@gmail.com

Received : Feb 23, 2022

Accepted : Apr 11, 2022

Published : Apr 15, 2022

Archived : www.jjgastro.com

Copyright : © Pasca S (2022).

Abstract

Introduction: Women hemophilia carriers (WHCs) are usually considered at low bleeding risk, but now this perception changed. WHCs previous treated with plasma-derived could have contracted post-transfusion HCV infection. Esophageal varices are one a lifethreatening complication of end-stage liver disease, HCV-related.

Methods: A comparison between a case of a WHC with lifethreatening esophageal varices needing emergency treatment with that of a severe male.

Results: No differences in terms of symptoms, treatment, and longterm prophylaxis between hemophilia patient and WHC were found.

Conclusion: In WHCs, a management like that performed in hemophiliac males is necessary to reduce bleeding risk, and a prophylaxis should be early started.

Keywords: gastric and esophageal varices; hemophilia; band ligation; prophylaxis.

Citation: Pasca S, Fasolato S, Polese L, Zanon E. A woman hemophilia carrier with life-threatening esophageal varices and a severe hemophiliac male: A comparison of two different case reports and a brief description of literature. Japanese J Gastroenterol Res. 2022; 2(6): 1074.

Case report

Hemophilia has always been considered a male disease. Its X-linked transmission made women exclusively carriers of the mutated gene, so all resources have been reserved for males with overt hemophilia. This consideration has therefore led erroneously to believe for a long time that Women Hemophilia Carriers (WHC) were asymptomatic and that hemorrhagic manifestations were very rare, almost anecdotal. Nowadays, however, this dogma is changing thanks to the numerous evidences that prove that WHC can also have bleeding, even severe [1]. Recent studies estimate that for each man with hemophilia A or B, 1.6 WHC can be identified [2], many of them may have a mild hemorrhagic phenotype, but there is no shortage of those with a moderate or severe one [3]. Major symptomatic bleeds are frequent in males with severe hemophilia, but in case of WHC data are not so clear. Plug et al. [4] reported a study on 274 hemophilia A/B carriers, with a mean FVIII/FIX level of 0.60 IU/ml, in which 8.5% experienced joint bleeds. The number of total events was equally divided among patients presenting factor level below 0.40 IU/ml, between 0.41-0.60 IU/ml and above 0.61 IU/ml. This underlines the fact that not only the patients who have lower plasma coagulation factor values are at hemorrhagic risk, but all carriers have a greater tendency to spontaneous bleeding. With this background in 2019 the Standardized Sub-Committees (SSCs) on “FVIII/IX and Rare Coagulation Disorder” and “Women’s Health Issues in Thrombosis and Hemostasis (T&H)” of International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) proposed a new nomenclature for WHC based on personal bleeding history and baseline plasma FVIII/IX level [5]. Up to date prophylaxis in WHC was unusual, but on-demand treatments with coagulation factor concentrates are needed in case of acute bleeding, even women then who have used plasma-derived (pd) drugs before 1985, the year in which the viral inactivation was introduced, may have contracted post-transfusion viral diseases such as hepatitis-C-virus (HCV) infection. This viral disease causes chronic inflammation of the liver that slowly evolves into progressive fibrosis from which cirrhosis, liver failure or hepatocellular carcinoma can develop. Portal hypertension, often present in case of cirrhosis, induces esophageal varices, one of the life-threatening complications of end-stage liver disease, and leads to many mortalities and comorbidities [6]. The management of the esophageal varices depends on the clinical symptoms presenting by each patient. In subjects at high risk of bleeding, use of prophylactic non-selective β-blockers with or without endoscopic ligation are recommended to prevent vessel rupture, instead in case of patients with acute bleeding. The different treatments include endoscopic sclerotherapy, ligation, banding, Trans-Jugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunts (TIPS) and pharmacological management, all equally effective in reducing the mortality rate [7].

No cases of WHC presenting esophageal varices and their treatment are reported in literature, here we describe the first of these compared with another case of a male hemophiliac.

Carrier - case

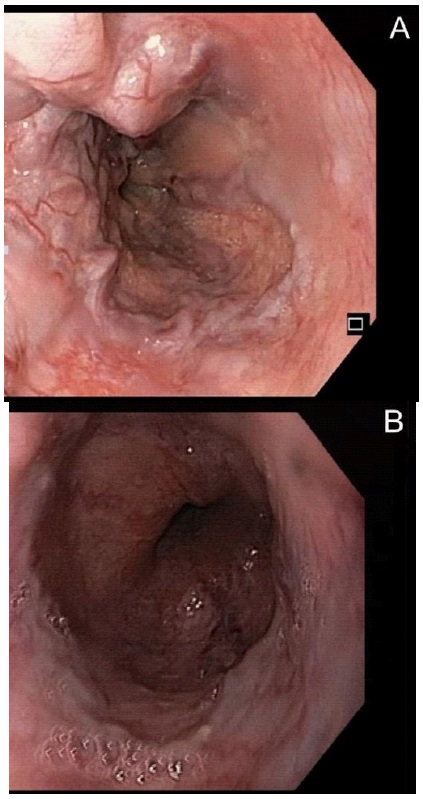

Female, 80-yrs-old, symptomatic woman with mild hemophilia A (FVIII 0.18 IU/ml), diagnosed in adulthood in the presence of severe menorrhagia and gum bleeding; genetic analysis revealed an intron 22 inversion. The patient was treated during her lifetime with pdFVIII concentrates on-demand to manage the acute frequent bleeds or in case of planned surgery. In September 1990 our patient was diagnosed with HCV infection (genotype 1a), later evolved into a decompensated cirrhosis (MELD Score 16, Child Plough C, Plt 41x109/l, INR 1.67, PT 42%, aPTT 38s) with esophageal (F3 CRS+++) and GOV2 gastric varices, causing a subsequent depressive syndrome. In March 2016 the patient was treated with ledipasvir+sofosbuvir for 24 weeks, with a complete viral eradication, but during this course of therapy she also developed hepatic encephalopathy and ascites. Following a major bleeding, in November 2017, our patient was hospitalized to perform the ligation of the esophageal varices. At the time of hemorrhage, she was always treated only on-demand with coagulation clotting concentrates. Three different consecutive procedures of band ligation were needed to solve bleeding, all performed under pdFVIII coverage, in addition to tranexamic acid, and according to the current guidelines with the goal of factor level of FVIII 0.80 IU/ml (35 IU/Kg) the day of band ligation and FVIII 0.50 IU/ml (25 IU/Kg) during the five days post-procedure.

The patient was then discharged and a long-term prophylaxis with pdFVIII drug (30 IU/Kg) three times a week was prescribed to reduce the bleeding risk. No recurrences nor complications at endoscopic subsequent follow-ups were reported. Given the marked hemorrhagic phenotype, our patient remained indefinitely in prophylactic treatment.

Comparison – case

Male, 72-years-old with severe hemophilia A (FVIII <1%), diagnosed in young age. The genetic analysis revealed an inversion of intron 22. In addition to hemophilia, the patient presented a type II diabetes being treated with oral hypoglycemic agents and the outcomes of poliomyelitis contracted in childhood. The patient was treated lifelong with pdFVIII concentrates on-demand. In the 1980s he was therefore diagnosed with HCV infection, followed by a severe liver cirrhosis (on 2014 MELD 11, Child Plough A).

In 2016 the patient was hospitalized due to sudden hematemesis, laboratory analysis showed: Hb 8.5 g/dl (normal range 13-18 g/dl), Plt 69x109 /l (normal range 150-450 X 109 /l), INR 1.49 (normal range 0.80-1.20), PT ratio 1.51(normal range 0.80-1.20), aPTT 83s (normal range 28-40s), while the gastrosco gastroscopy immediately performed revealed the presence of F2 esophageal blue varices (RWM++, CRS++) and clear signs of bleeding. He underwent a first successful endoscopic band ligation under pdFVIII coverage (45 IU/k) in addition to tranexamic acid to maintain the FVIII level 0.80 IU/ml the day of ligation procedure, reduced to 33 IU/Kg to ensure a FVIII level of 0.50 IU/ml in the ten days post-procedure without any bleeding reported. Subsequent follow-ups showed no relapses until February 2018, when following epigastric pain and melena the patient went to the Emergency Department. The gastroscopy performed at the admission therefore revealed a new presence of varicose cords F2B at bleeding risk (RWM+++-; CRS++--; HCS++--), while the laboratory analysis showed severe anemia (HB 4.4 g/dl) and thrombocytopenia (31x109 /l) treated with red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma transfusion.

A varices ligation was then planned and performed under FVIII coverage, using the same previous protocol. The treatment was successful, and the patient was discharged without complications.

A follow-up endoscopy performed in January 2019 did not show recurrence of varices, bleeding, or other adverse events. The patient was put on indefinitely prophylaxis with pdFVIII 30 IU/kg every other day to reduce the bleeding risk due to his coagulation disorder combined with the severe liver disease, and a long-term treatment with non-selective β-blockers to prevent other vessel ruptures were also prescribed.

These two cases are superimposable, but the real difference is that, while the man was a severe hemophiliac patient whose risk of bleeding was known and codified, despite being treated exclusively on-demand, the woman was instead an elderly carrier of mild hemophilia [5], in which the risk of bleeding was not well understood. All this therefore makes us understand that in women it is necessary to have an accurate medical and hemorrhagic history in order not to underestimate the risk of serious bleeding, which is always possible; associated with an accurate laboratory analysis necessary to define the level of factor to be reached to avoid spontaneous bleeding. Certainly HCV-related cirrhosis contributed to worsening the bleeding diathesis, but it is still worth noting how in similar situations a woman with a FVIII level of 0.18 IU/ml has had a hemorrhagic history like that of a man with a level of FVIII <0.01 IU/ml.

Raso et al. [8] compared women with hemophilia to mild hemophiliac males, but, as in our case, sometimes these carriers should perhaps be compared to moderate or severe ones.

Severe bleeding due to esophageal or gastric varices is a lifethreatening adverse event that can occur to patients in case of a concomitant presence of severe liver disease, before our report only two other publications [9,10] were available regarding the prophylactic endoscopic variceal ligation. The first described the case of a cirrhotic, hemophilia A, 40-year-old Japanese patient in which after four consecutive procedures the varices was completely eradicated, without recurrences in the following two years of follow-up, while in the second Japanese report two different cirrhotic patients underwent a total of nine different procedures undercover of coagulation factor concentrate and proton pump inhibitors. There have been no reports in the lit There have been no reports in the literature of management of hemophiliac women with esophageal or gastric varices. Ours is the first report that deals with this complication, and which highlights, in addition to what has already been described, the fundamental role of prophylaxis in preventing bleeding even in WHC.

Conclusion

In conclusion we can affirm that in case of symptomatic WHC, after having carefully evaluated their clinical and laboratory history, a prophylaxis with both standard and extended half-life concentrates should be started according to the medical and patient needs. In the future it will therefore be interesting to evaluate whether the new non-substitutive and subcutaneous drugs can also play an important role in the treatment of these patients.

Declarations

Acknowledgments: All of the authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interests: All authors have read and understood the journal policy on declaration of interests and declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Paroskie A, Gailani D, DeBaun MR, Sidonio RF. A cross-sectional study of bleeding phenotype in haemophilia A carriers. Br J Haematol. 2015; 170: 223-228

- D’Oiron R, O’Brien S, James AH. Women and girls with haemophilia:vlessons learned. Haemophilia 2021; 3: 75-81.

- Miller CH, Soucie JM, Byams VR, et al. Women and girls with hemophilia receiving care at specialized hemophilia treatment centers in the United States. Haemophilia 2021; 27: 1037-1044.

- Plug I, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Brocker-Vriends AH, van Amstel HK, van der Bom JG, van Diemen-Homan JE, et al. Bleeding in carriers of hemophilia. Blood, 2006; 108: 52–6.

- van Galen KPM, d’Oiron R, James P, et al. A new hemophilia carrier nomenclature to define hemophilia in women and girls: Communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 2021; 19: 1883–1887.

- Fransen an de Putte DE, Fischer K, Posthouwer D et al. The burden of HCV treatment in patients with inherited bleeding disorders. Haemophilia 2011; 17: 791-9.

- Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, et al. U.K. guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. Gut 2015; 64: 1680-704.

- Raso S, Lambert C, Boban A, et al. Can we compare haemophilia carriers with clotting factor deficiency to male patients with mild haemophilia? Haemophilia, 2020; 26: 117-121.

- Yamada M, Fukuda Y, Koyama Y et al. Prophylactic endoscopic ligation of high-risk oesophageal varices in a cirrhotic patient with severe haemophilia A. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998; 10: 151-3.

- Ishizu Y, Ishigami M, Suzuki N, et al. Endoscopic treatment of esophageal varices in hemophiliac patients with liver cirrhosis. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81: 1059-60.